The JRC – Joint Research Center of the European Community – commissioned a study on large-scale application of photovoltaics in the European landscape. The research project aims at providing policymakers with a culturally acceptable model for the implementation of new energy policies in Europe.

“IT’S THE CULTURE, STUPID!”

A recent study conducted by the Renewable Energy Unit of the Joint Research Center found that Europe shall commit to installing a total of 100,000 MW worth of photovoltaic systems by 2020, or about 6 times as much as currently deployed, in order to meet the target of 20% energy share from renewable sources, as mandated by Directive 2009/26/EC.

Most importantly, a major portion of the new capacity will have to be installed as very large, open-field power plans.

Much of the efforts to date by the PV industry and energy policy makers have been directed at creating efficient and economically viable models for the implementation of PV technology in the built environment.

Today, however, growing public opposition to large-scale PV installations is becoming the main obstacle to greatly expanding the PV installed capacity and to fulfilling the promises of independency from fossil fuels.

If EU member states are to reach the target mandated by the European Commission, then social, aesthetic and cultural concerns, not just technical ones, must be addressed as well.

Accordingly, the present “Concept for a Demonstration of Landscape Integrated Photovoltaics” aims at providing a culturally acceptable model for large-scale photovoltaic installations across the European landscape, in the context of the new energy policies of the European Community.

OBJECTIVES

The project aims at identifying opportunities to supply the anthropized environment with solar energy technology systems, in a way that is more efficient, less costly and more sustainable that current open-field PV systems.

Most importantly, the research attempts an investigation of both the cultural and the technological overlay of human activities, in order to identify strategies of occupations that are compatible with pre-existing uses of the land. The objectives of the present study for PHASE 1 – mid-term delivery – are listed below:

1. Cultural Framework: Defining a cultural framework of reference in the relationship between natural and built environment in the European context, and the role of culture as mediating protocol between Man and Nature;

2. Opportunities: Identifying opportunities in the development of land-integrated photovoltaic (LIPV) systems, particularly in regard to the broader social, environmental, and aesthetic aspects related to the implementation of large-scale technology infrastructure;

3. Methodology: Developing a design methodology, using customized analogue and digital tools, for qualitative and quantitative evaluation of relevant parameters and implementation of infrastructure components;

4. Site Selection: Selecting potential sites, based on opportunities of integration, cultural significance, and existing environmental emergencies that could benefit from the implementation of open-field photovoltaic systems.

5. Pilot Project: Selecting a emblematic site for a first pilot project, testing the methodology and providing an exemplar application of the design methodology for feedback from stakeholders.

2. CULTURAL FRAMEWORK

The central premise of the present study is that public opposition to large-scale PV installations may stem from widespread misconception on the historic transformation of the countryside across Europe over the past two thousand years.

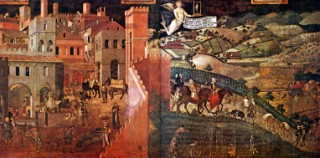

The idea of uncontaminated nature and the presumption of a boundary between the natural and the built environment, for instance, is largely a myth. Notwithstanding the idealistic division between the safety of man-made artefacts and the threat of wilderness, conveniently demarcated by a paper-like city wall in a Lorenzetti painting, the two domains have been interweaving from the very origin of mankind.

THE VANISHING LINE

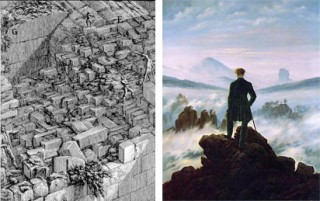

In the iconography of city walls, Piranesi offers perhaps the earliest account of a blurred boundary dividing architecture and nature, where it’s no longer possible, or even meaningful, to identify the distinctive qualities of either domain. Rows of orderly placed stone blocks undergo a series of gradual shifts and raptures, becoming the organic and porous substrate where roots take hold. The dichotomy between Nature and Architecture, Piranesi suggests, is only a matter of scale, or resolution, and it’s no more than a semantic distinction invented to serve a dialectic account of reality.

The dominant idea of landscape today is the one that was forged by the romantic tradition of uncorrupted nature, perhaps best illustrated in the famous painting The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich (1818): an idealized image of nature that serves a country’s national pride as well as the tourist industry, but where a vast energy infrastructure has no place.

SOCIAL AGENDA

In Edouart Manet’s Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (1862), a domesticated version of nature is the object of enjoyment by a group of middle-class young urbanites; this time, nature is not longer the place of production nor a threatening environment, but the backdrop for the entertainment and leisure of a newly established social class.

The appreciation for a rural environment divorced from its potential for creation of material value is a clear indicator of the progressive emancipation of urban societies from its earlier dependence on agricultural production.

The Land progressively loses its “guardians” and becomes increasingly vulnerable to abuses or plain obsolescence.

THE OTHER HALF

As a remarkable effect of the idealization of nature, the European identity clings to a handful of idealized natural reserves and architectural treasures that became global cultural icons.

Meanwhile, the massive loss of natural land to the combined effect of relentless expansion of urban areas, modern infrastructures and extraction of natural resources over the past 150 years has been removed from the collective consciousness.

As advanced societies become increasingly dependent on the mass production of industrialized agriculture and vast mining operations, the places of production and extraction are being gradually relocated in remote areas of the planet, often outside the control of environmental agencies and away from public scrutiny.

CITY WALL IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Interestingly, even in the master plan for Masdar City by Foster and Partners, arguably the most advanced vision for a sustainable city currently under construction, the places of production (energy, water purification, waste management) are clearly separated from the places of consumption by a city wall and they are conveniently invisible to the very people that entirely depend on these systems for their survival. The city planner makes no effort in integrating these two realms or in reconciling the vast array of mechanical systems with its environment.

SECURITY AND DYSTOPIA

In the future, issues of security and scarcity of natural resources will require a new regime in policing the landscape and separating once again the territories controlled by dominating cultures and corporations from the ones that are subjected to the plundering of rough states and terroristic organizations. In Winterbottom’s Code 46, large swaths of land are left unguarded, interstitial places between intensively monitored cities, where one can trade freedom for protection (and control) or choose a life in the afuora, without the digital tracery of technology, and without memory.